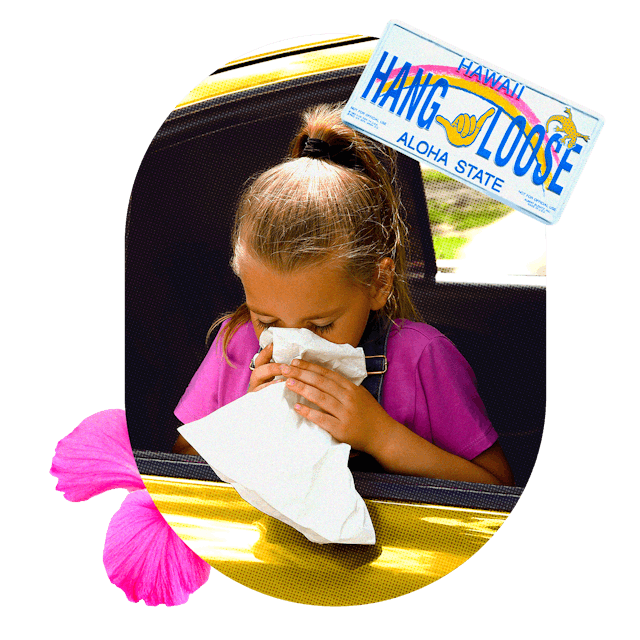

My Kid Gets Car Sick Every Time We Go For A Ride. Help!

A pediatrician offers the pointers you need if you’re tired of cleaning puke out of the floorboards.

For many parents, the only place they can get their baby to fall asleep is in the car. But something happens as they get older; they get all fidgety and start kicking the back of the seat and asking are we there yet? a million times. Or, worse, they get queasy every time they get in the car, making even a quick ride to the store a nightmare. And a full-fledged road trip? Forget about it. You’re lucky if you can make it out of the driveway without hearing the tell-tale sound of your kid retching in the backseat, much less across state lines.

If this sounds like your family and you’re wondering how to put an end to these unfortunate bouts, you came to the right place. To learn more about kids and car sickness, Scary Mommy spoke with Dr. Christina Johns (“Dr. Christina”), a pediatrician specializing in pediatric emergency care, a senior medical advisor at PM Pediatric Care, and a regular contributor to the medical talk show Doctors Call.

Here’s what she had to say.

Why do people get car sick?

Car sickness is a type of motion sickness, and, as the name implies, it happens when our bodies experience a lot of movement. But not just any movement, like walking or running — Johns explains that motion sickness usually occurs when you’re in the car or on a plane or boat because of the conflicting information of motion and stillness that your brain receives from your eyes, ears, muscles, and joints. This inconsistent signal to the brain is what causes many people to experience symptoms, including nausea, dizziness, and headache.

Why do a lot of kids get car sick?

Anyone is susceptible to experiencing motion sickness — in fact, according to the Cleveland Clinic, an estimated one in three people experience it at some point. But women and children especially are affected, says Johns. “The reason kids are a little more prone to get carsick than adults is that their view of the outside is often more obscured either due to their placement in the back seat or their inability to see out of the windows because of their height. As permanent passengers, children are also more likely to be reading, looking at a device, or playing with a toy, creating more of a discrepancy between what they feel and what they see,” says Johns.

What can parents do to help prevent car sickness?

Not having your child ride in the car probably isn’t an option, but the good thing is that, in most cases, there are simple things you can do to help prevent or ease car sickness. Riding in the front seat is a great option for older kids who meet the safety requirements since they can see directly out of the front window, easing that conflicting information to their brains. But because kids are often backseat passengers, that’s not always possible.

Other tips for preventing car sickness include:

- Stay properly hydrated.

- Avoid smoke or fumes.

- Keep the car cool (roll down the windows or turn up the A/C).

- Sleep, if possible.

- Use acupressure bands like Sea Bands.

- Suck on ginger candy.

- Eat small snacks, frequently.

- Distract yourself/child with music or activities.

“If your child starts to get carsick, ask them to look out the window, if they can. Seeing moving objects outside may stabilize the sensory input to their brain. It might be a good idea to pull over and let them walk around outside until they feel alright again. If you know that your child is prone to car sickness, do not feed them a large meal before traveling, as this could contribute to nausea and even vomiting,” says Johns.

In severe cases or for travel, she explains, parents can ask their child’s pediatrician about using over-the-counter medications like Dramamine. Always consult your child’s doctor before reaching for meds like this, though, and make sure you’re using the correct dosage based on your child’s age and/or weight.

This article was originally published on